We have long been interested in assessing the historical extent of floodplain meadows and have worked with a range of individuals over the years who are researching their local meadows in terms of their historic extent. This work requires in-depth research, exploration of the archives and a good knowledge of the local area and is therefore quite specialised. However last year, we worked with Fjordr Ltd, which had previously undertaken related work on the historic character of watercourses to explore the possibility of using easily accessible GIS maps to identify the extent of floodplain meadows in two pilot catchments.

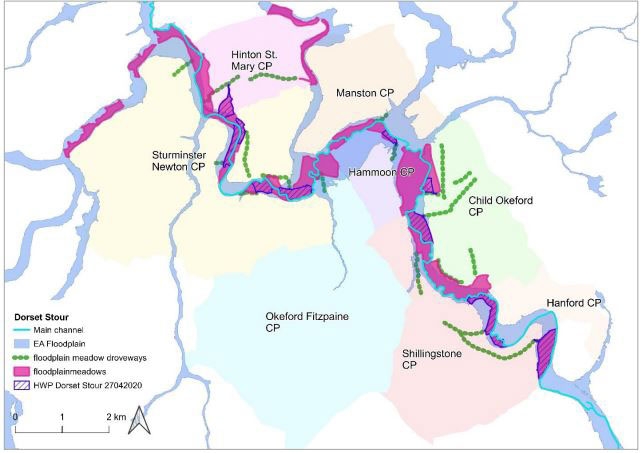

During their previous project on the Dorset Stour, meadows with distinctive funnel-shaped entrances from droveways were identified in the floodplain, echoing the entrances seen where roads and droveways enter a common to facilitate the movement of livestock. These funnel-shaped meadows generally look quite different to the fields surrounding them, which in turn seem to respect their often sinuous, irregular boundaries, suggesting that the funnel-shaped meadows pre-date the more organised enclosed fields that abut them.

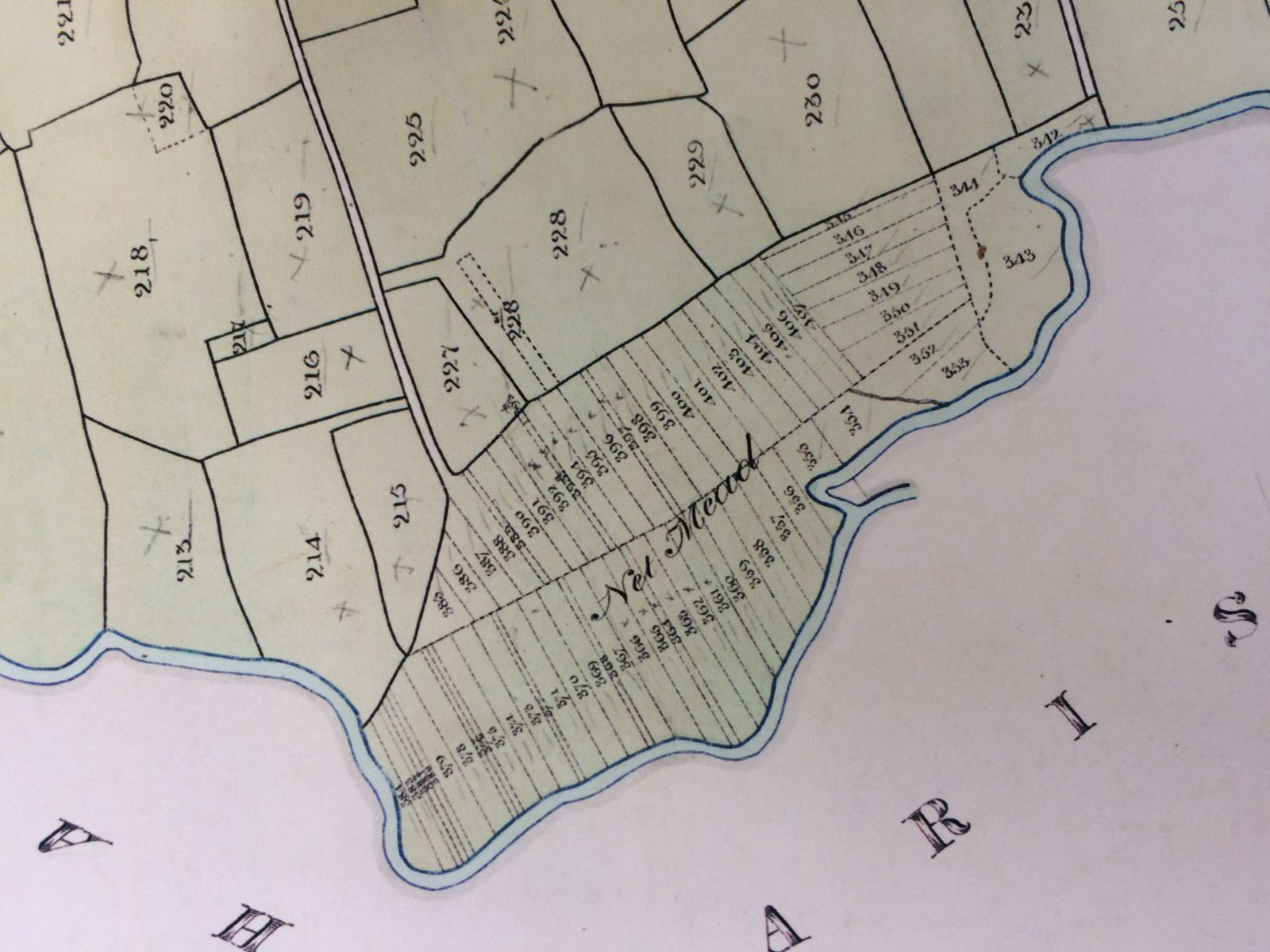

Furthermore, on tithe maps from the 1840s, the funnel-shaped meadows are often sub-divided into multiple strips demarcated by dotted lines that fit within the boundaries of the meadow. The system of dividing up meadow into strips to allocate hay followed by common grazing on the aftermath reflects a practice dating back to the medieval period.

The project focussed on using GIS to draw together map-based evidence to estimate how much of a floodplain in a river catchment was floodplain meadow in the past based on the identification of these funnel shaped meadows; how floodplain meadows were distributed relative to parishes; and to explore whether the amount of floodplain meadow might be related to the size of previous populations.

Looking at seven parishes on the Dorset Stour, the project identified additional floodplain meadows managed as commons, and clarified the extent of those identified previously. The methodology was then applied successfully to eleven parishes on the Windrush, Thames and Cole. In both areas, the methodology confirms the persistence into nineteenth century mapping of a distinctive form of floodplain meadow with clear and quite consistent morphological features. Sufficient of these are shown subdivided into doles in tithe maps in the 1840s to indicate that they were managed as commons by allocating strips to individuals for hay followed by grazing of the aftermath. The need to move animals to and from the floodplain meadows gave rise to their funnel-shaped entrances accessed via droves connecting them to settlements. The importance of these droves and meadows caused them to be maintained while surrounding land was enclosed, though in many cases enclosure and private ownership subsequently encroached upon them.

Net Mead adjacent to the Dorset Stour in Child Oakford parish. The 1840 tithe map shows a floodplain meadow in the form of a funnel shaped field served by a lane, subdivided into strips. Dorset History Centre, Ref No T/CHO. Image by Fjordr

Net Mead adjacent to the Dorset Stour in Child Oakford parish. The 1840 tithe map shows a floodplain meadow in the form of a funnel shaped field served by a lane, subdivided into strips. Dorset History Centre, Ref No T/CHO. Image by Fjordr

The Dorset Stour

The GIS enables the area of historic floodplain meadow managed as commons to be compared with the modern area of the floodplain.

Floodplain Meadows (purple) identified along the Dorset Stour. Droveways are marked in green. There are no known floodplain meadows now remaining in this area that still contain the typical plant community. HWP relates to the previous Historic Watecourses project undertaken on the Stour and is available here

Floodplain Meadows (purple) identified along the Dorset Stour. Droveways are marked in green. There are no known floodplain meadows now remaining in this area that still contain the typical plant community. HWP relates to the previous Historic Watecourses project undertaken on the Stour and is available here

The approach has shown that each parish had at least one floodplain meadow managed as commons. Some parishes had several, though this may reflect the presence of multiple historic settlements within a parish, some of which may not have survived to the modern period. Broadly, it appears that each settlement or parish had its own share of floodplain; this impression is reinforced by the close relationship between floodplain meadows managed as commons, their settlements, and the droveways that connected them.

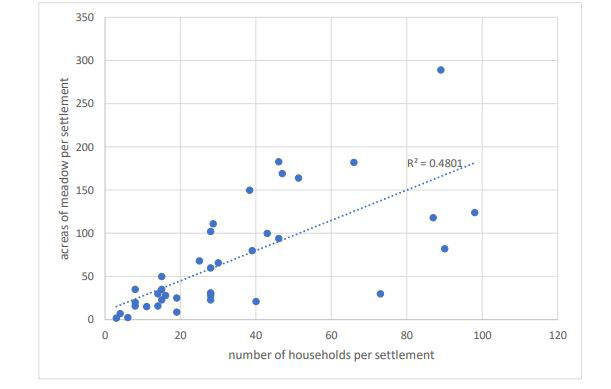

There appears to be a relationship between the size of population (recorded as number of households) and the extent of meadow (in acres) recorded in the Domesday survey, where meadow is understood to mean ‘land susceptible to flooding as it was next to water’. Moreover, the proportion of meadow recorded in Domesday from settlement to settlement among those selected here is – in some instances – in close proportion to the area of floodplain meadow that has been identified. It might be tentatively suggested that there seems to be a correlation between the floodplain meadows identified in this study and the landscape of the Dorset Stour in 1086. There appears also to be a relationship between the geology of the Dorset Stour, the acreage of meadow and number of households recorded in Domesday, which may be attributable to the way that geology constrains the floodplain.

Scatterplot showing the relationship between number of households and acreage of meadow recorded in Domesday (Dorset Stour).

Scatterplot showing the relationship between number of households and acreage of meadow recorded in Domesday (Dorset Stour).

The Thames and tributaries

Looking at the Thames tributaries study area, comparison of the Domesday data for meadows with the identified floodplain meadows suggests that meadows increased in size after 1086, perhaps reflecting the increase in medieval population prior to its decline in the fourteenth century. There are, however, examples where the area of meadow does not appear to have varied much between the medieval period and the nineteenth century, which may reflect constraints on the floodplain acting as a limiting factor. As on the Stour, it was found there is a relationship between the number of households and the amount of meadow recorded in Domesday.

The project has shown that floodplain meadows once managed as commons persist in the landscape even where they are previously unrecorded. In some cases, their form and topographic features survive even if the habitat has been extinguished by intensive agriculture. Where they don’t survive physically, the presence of floodplain meadows can be traced in historic maps, documents, and archive data. However, old maps don’t speak for themselves: by the time the first detailed, precise and widely available maps were made – notably tithe maps in the mid-nineteenth century and large-scale OS maps in the late nineteenth century – floodplain meadows had already disappeared in some places due to enclosure or other encroachment. In these cases, identification of former floodplain meadows requires interpretation based on multiple sources.

Caution is required about the weight placed upon a few maps and geographical accounts given a history of floodplain meadows stretches over a millennium, if not longer, but there are sufficient sources for the earlier extent of floodplain meadows to be confidently mapped in many catchments. The approach offers a robust and transparent method for evidencing the former presence and extent of floodplain meadows managed in common, both locally and regionally. In turn, this offers a way of quantifying loss and rarity; but it is also a way of flagging potential sites for restoration, especially where their physical features still survive. The method also provides a means of directly integrating restorable meadows into catchment management alongside other opportunities for nature-based solutions.

The project has shown that floodplain meadows are not just physical things: they are the embodiment of cultural practices carried out by communities over many generations. They combine both tangible and intangible heritage. This character is underlined by their demonstrable relationship with the parishes and settlements that gave rise to them, and the droves that were key to their accessibility and gave them their distinctive form.

The results of this project support the view that floodplain meadows were both widespread and central to the organisation of the rural economy for at least a thousand years. Common governance, co-creation and public access were fundamental to floodplain meadows in the past, and perhaps also to their restoration and maintenance in future. The form of floodplain meadows surviving in the field and in documents embodies centuries of traditional knowledge: can we learn from the knowledge embedded in our historic landscape as we attempt to re-establish more resilient habitats, places, and communities?

For the full final report see Firth, E. and Firth, A., March 2022, Historic Extent of Floodplain Meadows: Dorset Stour and Thames Tributaries. Report by Fjordr Ltd. for the Floodplain Meadows Partnership.

More details about the method here: Historic Watercourses: Developing a method for identifying the historic character of watercourses: River Stour, Dorset

Historic Floodplain Meadow sites map developed using this method is here

More about the project here

Subscribe to make sure you don't miss out.