Our traditional floodplain hay meadows are a haven for biodiversity, but they are also part of our agricultural landscape and depend on the annual cycle of haymaking and aftermath grazing to maintain their value. These meadows show characteristic seasonal patterns of growth and flowering – known as phenological progression – and it’s important to work with these natural processes to get the most out of our heritage meadows for both agriculture and wildlife.

Photo by Vicky Bowskill

Photo by Vicky Bowskill

Seasonal growth patterns

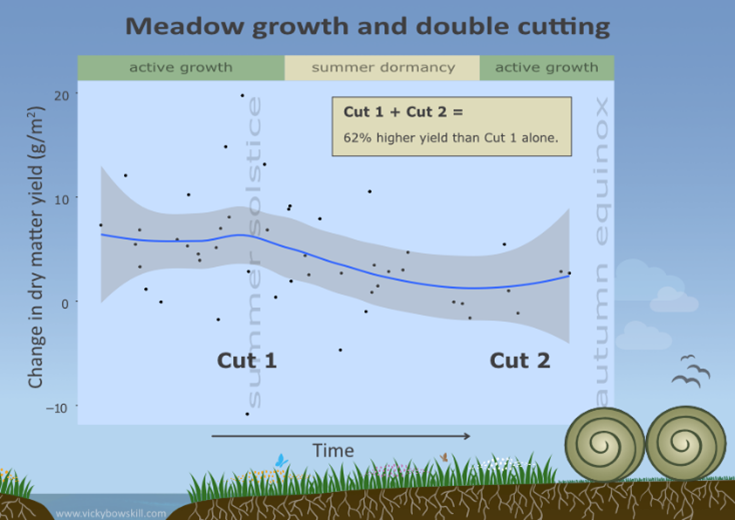

Most of the plant growth in meadows happens between May and September, though this timing is heavily influenced by both temperature and rainfall, which can vary considerably each year. The overall trend is a period of active growth through May and June, peaking around mid-summer or a bit after. This is followed by a period of summer dormancy, in which growth tails off and even starts to die back in the process of senescence, before picking up again for a second flush from late August and through September. But what causes these changes? And how does haymaking influence them?

The annual cycle of most plants is to produce leaves, flower, be pollinated and produce seed. There will also be plenty of growth going on underground, with new buds giving rise to the next leaf rosettes, and an increase in rhizomes and bulbs. The intense active growth during spring and early summer culminates in flowering and seed-set in many species around mid-summer. That’s what makes a June meadow such a colourful and inspiring place (or possibly an irritation if you suffer from hay fever).

Plants grow extra roots and leaves in spring to provide the resources needed for this intense growth. These additional tissues enhance photosynthesis and absorption of the nutrients and water they need. After this mission has been accomplished, the meadow basically takes a breather. The spring-formed roots and leaves may die off and the meadow changes from the intense bright greens of spring to the dark mellow green of summer, made up of many fibrous spent flower stalks and old leaves. The rhizomes store nutrients accumulated by the young leaves, while the longer-lived roots take up water to see them through the drier months of summer.

After this period of calm and recuperation, provided there is enough rain to fuel it, a second flush of active growth kicks in later in the summer and into early autumn. New roots and leaves form, which may survive through to the following spring. If you have a lawn, you will have noticed the need for extra cutting at this time of year.

The time for haymaking

These natural growth patterns also indicate the likely nutrient status of the hay crop. During active growth, plants are taking up lots of nutrients and using them to build leaves, flowers and seeds. But once plants enter a more dormant phase – when seeds have been shed and nutrients have been stored away in underground roots, rhizomes and bulbs – the concentration of protein and other nutrients in the aboveground plant tissues can fall dramatically. The hay becomes more fibrous and less palatable for livestock.

By working with these growth cycles, it’s possible to capture a more nutritious crop and also to increase the yield by stimulating growth and flowering. Cutting during a phase of active growth can trigger a pulse of compensatory regrowth through increases in photosynthetic rate, higher growth rates, increased branching and tillering and reallocation of nutrient stores from rhizomes and roots to shoots.

Whilst cutting before nutrients have been expended in seed shed may interrupt the plant’s reproductive cycle, a further period of re-flowering and clone formation can be stimulated. So rather than the cut preventing flowering, it may in fact extend it in some species and this can contribute to a prolonged availability of late-season nectar sources for pollinators. These hay meadow plants have thrived under this cycle of annual hay cutting for centuries and don’t need to set seed every year. In fact, some of the individual plants in permanent meadows can be several decades, or even centuries, old demonstrating that new recruits from seed are only needed once in a blue moon.

The double cut

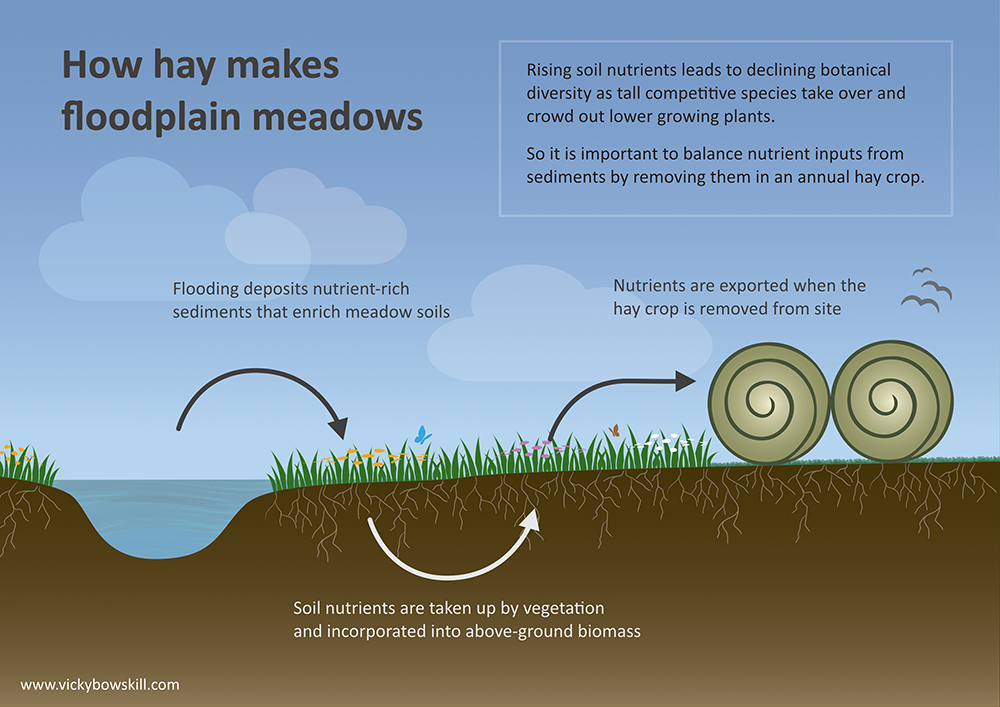

Delivery of nutrients by floods in these naturally fertile floodplain meadows can be a problem for maintaining botanical diversity if they are allowed to accumulate, allowing tall competitive species to take over (see Figure 1). One way to control this problem is to take a double hay cut – harvesting in the summer and again in September – removing nutrients during the two peak periods of nutrient uptake from the soil. This also provides an extra crop in a win-win for both agriculture and nature.

Early results from ongoing research have shown that if you time your first cut right by doing it before the summer dormancy and take a second cut in September, this can result in 62% higher yield compared to only cutting in mid-summer (see Figure 2). And increased yield means not only extra hay for livestock, but increased removal of soil nutrients. That’s because the earlier cut stimulated growth, causing plants to invest more resources in their aboveground tissues through the rest of the season. Ongoing research will reveal the difference in nutritional value between early and late cuts.

Even if you don’t actually take that second cut, this still demonstrates how much extra standing crop is available in your aftermath grazing if you time the early hay cut well. However, aftermath grazing doesn’t remove much nutrient from the soil, as most of it is simply deposited straight back to the soil via animal waste. So if you really need to reduce soil nutrients to balance your meadow, it’s important to cut and remove the hay from site.

Changing seasons

Traditionally floodplain meadows would have been cut around mid-summer – late June – during the summer active growth phase and just before the peak of aboveground biomass. They have been managed in this way for hundreds of years and the species that thrive in them are well suited to this pattern of seasonal haymaking. Unlike drier meadows, where the nutrients removed each year in the hay crop need to be manually replaced, these wet floodplain meadows receive nutrients every time they flood. So the use of a well-timed annual hay cut is critical to maintaining the nutrient balance that best supports their characteristic botanical diversity. With advancing seasons and changing patterns of flooding and drought, the ‘best time’ to remove hay is likely to vary from year to year and a pattern of flexible, adaptive management may be more appropriate than rigid date-driven controls. With sensitive management these meadows can form a valuable, low-input part of a sustainable, nature-friendly farming system that can contribute to food production whilst also maintaining a wealth of biodiversity.

Figure 1: The floodplain meadow nutrient cycle

Figure 1: The floodplain meadow nutrient cycle

Figure 2: The floodplain meadow growth cycle

Figure 2: The floodplain meadow growth cycle

Words and images by Vicky Bowskill.

Further reading