Vicky Bowskill

Audio version (5m32s)

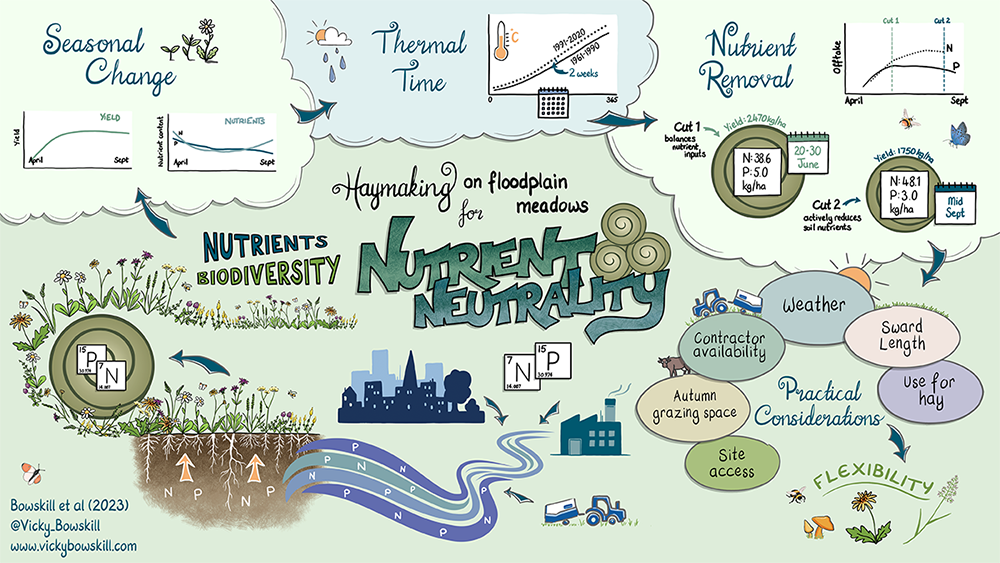

Floodplain meadows are an ancient part of the multi-functional agricultural landscape of Britain that provide not only food and fodder, but also essential services such as flood prevention and carbon storage. Their high level of biodiversity is shaped by the annual cycling of nutrients through the deposition of nutrient-rich river sediments, which adds nutrients to meadows soils, and haymaking, which takes nutrients back out. In this article we discuss the Hay Days project which looks at how the timing of haymaking can change how fertile this agricultural land is and how much biodiversity it can support.

As well as supporting up to 40 species of plant in each square metre and all the other life that depends on them, floodplain meadows can store vast amounts of carbon in their deep humic soils, help prevent flooding, improve water quality and provide a nutritious hay crop. An integral part of British rural life and livelihoods since before the Domesday Book, they also offer endless inspiration and a host of health and wellbeing benefits. But almost all of these meadows have been lost since World War II and now only about 3000 hectares remain in Britain. So meadows need our help – and we need theirs.

The rich biodiversity found in floodplain meadows has come about largely as a result of the annual cycling of nutrients through the meadow via flooding and haymaking. Nitrogen and phosphorus are two important nutrients for both plants and livestock – but when in excess they can act as pollutants in soil and water. Large quantities of these minerals find their way into our rivers in runoff from urban and industrial areas, from intensive agriculture and via sewage outlets. If you watched the recent BBC/OU Wild Isles series with David Attenborough, you may have heard the shocking fact that every single one of our rivers in the UK is now polluted in this way. To combat this, some rivers in the UK now have nutrient neutrality targets for new developments. This means that planners must find ways to mitigate additional nutrients that make their way into rivers from any new development in at-risk catchments.

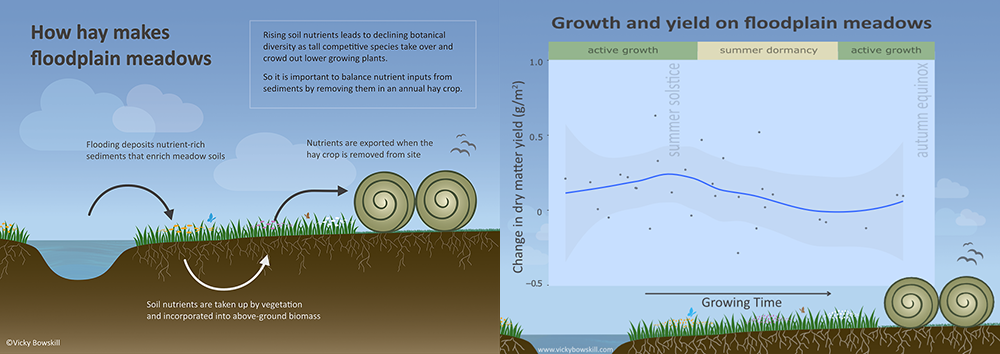

These river-borne nutrients are deposited on floodplain meadows in flood sediments. These sediments provide a source of natural fertility, for which floodplain meadows have long been valued as productive agricultural land that doesn’t need artificial inputs of fertiliser to produce a healthy crop.

But if the minerals that arrive in each flood are allowed to build up in the soils to excess, then tall competitive species take over these meadows and their botanical diversity falls . Therefore, removing these minerals via the nutrient-rich hay in an annual harvest is essential to maintaining high botanical diversity.

A matter of timing

Floodplain meadows are a seasonal system and the concentration of nutrients in the soil and hay changes as the growing season progresses. This means that the timing of haymaking can have a large influence on the control of these nutrients. Nitrogen and phosphorus are taken up rapidly during the early part of the growing season as new shoots are actively growing. This accumulation reaches a peak around mid-summer before a more dormant phase that follows flowering and seed set, when hot dry weather is more likely to dominate. A second flush of active growth happens in early autumn when the rains return.

Figure 1 (left): Nutrient cycling in floodplain meadows

Figure 1 (left): Nutrient cycling in floodplain meadows

Figure 2 (right): Annual growth curve of floodplain meadows

Regulations sometimes restrict hay from being made until mid-July – a month after the mid-summer peak, ostensibly to protect any ground nesting birds that may be present. These restrictions may have been suitable in the 1980s when they were first introduced but, since then, the relationship between calendar date and thermal time (the rate at which heat builds each year) has advanced by about two weeks because of climate change and plant growth has advanced with it. So the calendar dates that restrict haymaking now effectively fall later in the botanical growth cycle and therefore may be contributing to declining botanical diversity through changes in nutrient cycling.

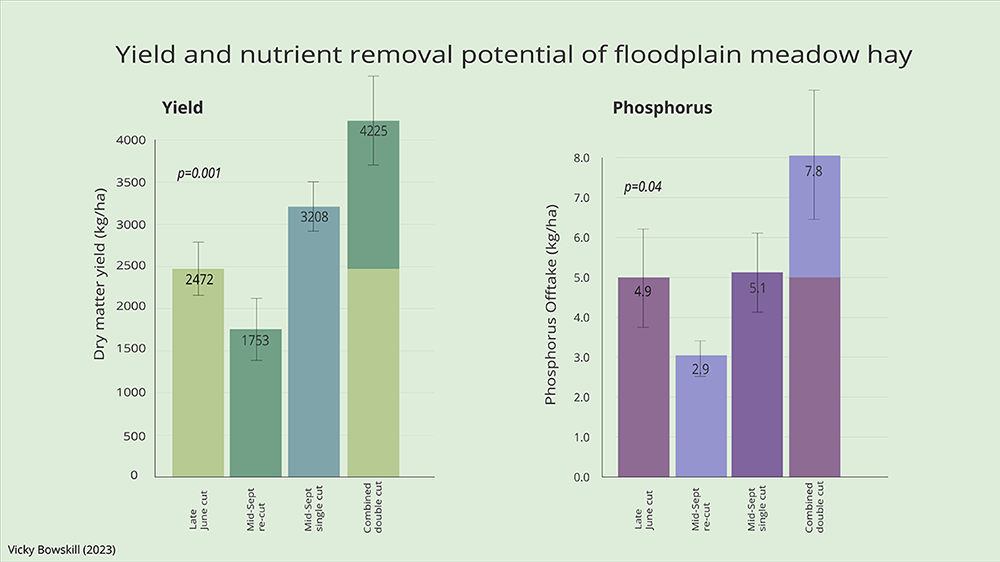

The optimal time for a summer hay cut from the perspective of maximising nutrient removal and yield is currently 20-30 June in central England and this is likely to continue to become earlier under climate change. The summer harvest removes around 0.5 g m-2 of phosphorus and 3.9 g m-2 of nitrogen and these amounts roughly balance the sediment inputs for a typical meadow, though those vary depending on local circumstances.

Whilst it is common in the UK to graze the autumn regrowth after a summer harvest, grazing removes only a small amount of additional nutrients, as much of what the animal eats is quickly redeposited in dung and urine. Taking a second harvest in September can remove a further 0.3 g m-2 of phosphorus and 4.8 g m-2 of nitrogen. Double cutting is therefore an effective way to reduce soil nutrients to enhance meadow restoration. Taking the first cut in mid- to late-June, rather than mid-July allows a longer period for regrowth and delayed or reflowering later in the summer. This extends nectar resources for pollinators and allows for the maximum level of nutrient offtake in the double harvest.

Figure 3: Thermal time has advanced by 2 weeks between 1961 and 2020

Figure 3: Thermal time has advanced by 2 weeks between 1961 and 2020

Figure 4: Nitrogen and phosphorus offtake potential in floodplain meadows hay

Figure 5: Yield and phosphorus offtake potential of floodplain meadows are compared for a late-June summer cut, a second cut in mid-September, a single late cut in September and the combined June and September cuts in a double cut system.

Figure 5: Yield and phosphorus offtake potential of floodplain meadows are compared for a late-June summer cut, a second cut in mid-September, a single late cut in September and the combined June and September cuts in a double cut system.

Practicalities

In the course of this project, farmers and meadow managers were consulted about the practicalities they face when making hay – and there are many things to consider. The primary one is always the weather. A window of three to four dry days is needed for hay to be cut, turned, baled and transported to dry storage. Increasingly unpredictable weather can make this difficult to achieve. Many farms rely on contractors for the harvest and that can be difficult, especially when date restrictions concentrate demand for these services. Many remaining meadows are small and fragmented, making it difficult to access them with modern machinery and also making it hard to compete with larger holdings for in-demand contractors. Taking a double harvest can double many of the costs and difficulties with achieving this. Sward length may make it difficult to take a second harvest if the grass is too short for the baling machinery available. Shorter material may need to be wrapped for haylage, bringing with it the use of plastic wrap and the extra cost of hauling a moist crop.

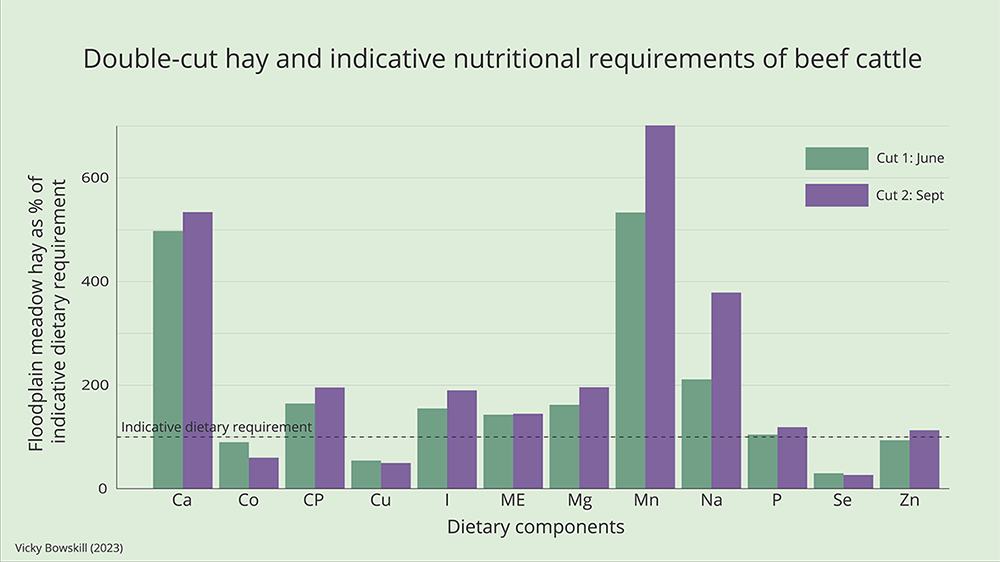

In regenerative pasture-fed systems, autumn grazing space may be a higher priority than a few extra bales of hay. And if you do make extra hay, there needs to be a use for it, either on farm or through a customer base. Opinions have varied about the nutritional quality of meadow hay harvested at different times, but this study has found that the nutritional content remains high in the second cut and provides well-balanced nutrition for most livestock.

Figure 6: Nutritional profile – including dietary minerals, crude protein (CP) and metabolisable energy (ME) – of first and second cut hay as a percentage of the typical dietary requirements of beef cattle. Dietary requirements can vary widely depending on the breed, age and reproductive status of the animal and these figures are indicative only.

Figure 6: Nutritional profile – including dietary minerals, crude protein (CP) and metabolisable energy (ME) – of first and second cut hay as a percentage of the typical dietary requirements of beef cattle. Dietary requirements can vary widely depending on the breed, age and reproductive status of the animal and these figures are indicative only.

The needs of ground nesting birds, such as curlew, are also an important consideration in floodplain meadows and respondents reported successful relationships with local birding groups. These groups have assisted many farmers to identify any nests so they can be protected without having to delay haymaking unnecessarily and compromise the botanical diversity of the whole meadow.

Despite the many potential difficulties in managing the hay harvest, most farmers who took part were highly motivated to support nature to thrive on their farm. Most were already doing a lot to help and were keen to try new ideas that might improve the nature value of the land they manage. This work is often prioritised without any direct recompense, but balancing the books is a necessity and recognition of this fact through agri-environment schemes is essential to support the adoption of the most appropriate practices in these sensitive landscapes.

Nature conservation and farming do not need to be mutually exclusive and floodplain meadows are a prime example of a system that can fulfil the aims of both, and more, if managed in a way that includes well-timed haymaking at each site.

Reference

Bowskill, V.; Bhagwat, S.; Gowing, D. (2023), Depleting soil nutrients through frequency and timing of hay cutting on floodplain meadows for habitat restoration and nutrient neutrality, Biological Conservation, Volume 283, 110140, ISSN 0006-3207, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2023.110140